The Distinct Brain Patterns of Liberals and Extremists

Imagine a simple brick for a moment. Now, take two minutes to jot down all the possible uses for that brick.

How did you fare? Perhaps your first thought was building a house, followed by ideas like constructing a school, and then maybe more unconventional uses such as a doorstop, a paperweight, a plant pot, or even as a coffee grinder. A few of you might even have ventured into darker territory, considering it a potential weapon.

Your answers to this experiment, known as the Alternative Uses Test, can reveal a lot about your generative flexibility, or the ability to think creatively. Interestingly, this flexibility may also correlate with your political beliefs.

Enter The Ideological Brain, the innovative work of Leor Zmigrod, a political psychologist and neuroscientist who explores whether our ideological differences stem from our brain functions.

According to Zmigrod, political ideologies can significantly shape cognitive processes. Individuals on the extreme left and right not only possess different thought patterns compared to moderates, but also display distinct brain activity. For example, research from 2011 by a team at University College London showed that the right amygdala, responsible for processing negative emotions, was larger in individuals with conservative views.

In a series of interactive mental challenges, Zmigrod examines cognitive patterns linked to rigid ideological thinking. If you’re curious about the brick exercise, those who found it challenging are more likely to hold extreme political views. She posits that ideologies can oversimplify our world perception, reducing our capacity to appreciate nuanced details.

Some of her conclusions might stir controversy. For instance, in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, where 52 percent opted to leave the EU, her experiments indicate that people with higher levels of cognitive rigidity—meaning their reluctance to alter their views in light of new evidence—tended to lean towards more nationalistic sentiments and were likelier to vote for Brexit.

While cognitive rigidity is a trait observed in both far-left and far-right individuals—ranging from communists and fascists to religious extremists and conspiracy theorists—Zmigrod’s studies reveal that the most intellectually flexible individuals are typically non-partisans who lean towards the left. This finding may unsettle a portion of the electorate but highlights a crucial distinction between adaptable and inflexible minds.

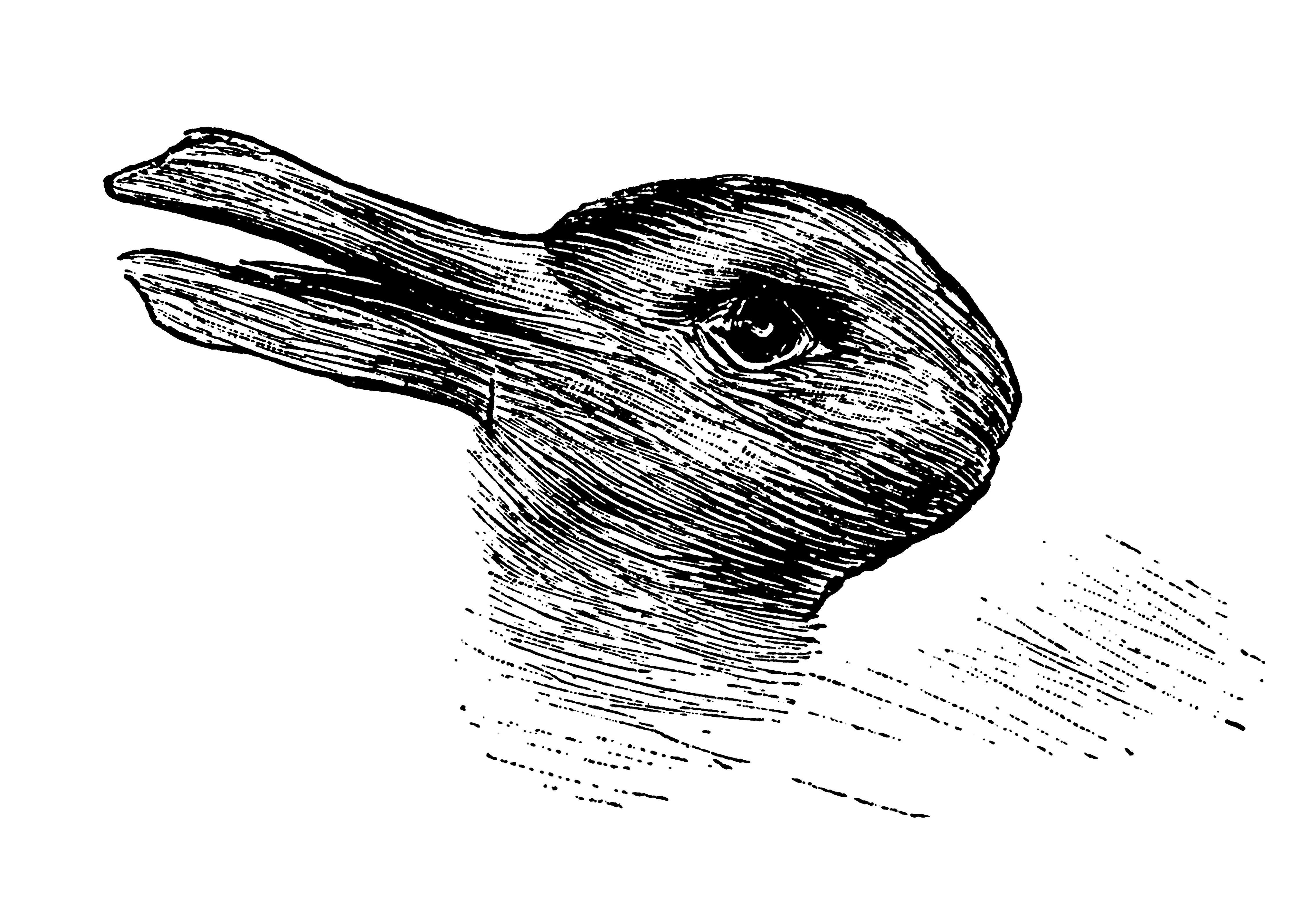

Reflecting on the past, Zmigrod recalls a groundbreaking cartoon from 1892, depicting dual images of a rabbit and a duck—a challenging visual for those with rigid thought processes. Liberals can easily perceive both images, while those with extreme views often see only one and staunchly defend their perspective.

Zmigrod also builds upon the pioneering research of Else Frenkel-Brunswik, who conducted fascinating experiments on children in the mid-20th century, particularly focusing on those labeled as the “most prejudiced” or “most hateful.”

In one compelling study, she presented a series of color cards to children, observing how the more prejudiced groups failed to recognize color variations, often recategorizing different shades as simply “red” and favoring clear, black-and-white classifications while disregarding subtleties.

This indicates a troubling propensity: those with entrenched biases may ignore evidence contradicting their worldview. It mirrors experiences in data journalism, where despite substantial evidence presenting declining crime rates since the 1990s, some individuals remain unconvinced, even when living in relatively safe environments.

While some individuals are naturally inclined towards rigid thinking, it can be exacerbated by external stressors, pushing their views to extreme positions.

Zmigrod writes compellingly and engagingly, though some of her scenes, like a friendly debate with historical figures such as Napoleon and Darwin, may appear unusual.

Ultimately, her core argument is critical in our increasingly polarized world: recognizing rigid thinking in ourselves is essential, and we must make an effort to consider alternative perspectives. It’s worth contemplating what an “anti-ideological brain” might entail.

Post Comment