Revealing Insights into the Sahara Desert

In an intriguing exploration, Judith Scheele presents a captivating and thought-provoking examination of the Sahara, the world’s largest hot desert. This book is set to attract readers who have a general interest in the Sahara and the diverse communities that reside within it. It particularly resonates with those critical of Western narratives surrounding issues like immigration, capitalism, and colonial pasts.

From the outset, Scheele, a social anthropologist based in France, challenges Western perceptions with phrases like “high-tech Euro-American imperialism”. Yet, she soon delves into the fascinating geology and ecology of the desert, revealing unexpected insights.

Surprisingly, the Sahara harbors vast reserves of fresh water, with the Nubian Sandstone aquifer system holding an astounding 150,000 billion liters and the Northwestern Sahara aquifer system containing an additional 50,000 billion liters. The Bodele Depression in Chad, measuring 310 miles long, emits around 700,000 tons of nutrient-rich dust daily, contributing to the Sahara’s yearly output of 1.7 billion tons of dust. Scheele emphasizes the importance of this dust in supporting the fertility of oceans and rainforests.

Notably, the Bodele Depression is also where archaeologists discovered the world’s oldest hominid skull, estimated to be approximately seven million years old, challenging the Rift Valley as the cradle of humanity.

While Scheele is outspoken about her views, offering both criticism and unexpected insights, she raises significant concerns about the terminology surrounding desertification and global anti-desertification initiatives. She argues that such programs mischaracterize deserts as problematic environments rather than as complex ecosystems and often harm the local pastoralist communities.

Historically, deserts have been viewed as the opposite of civilization, with inhabitants labeled as barbaric. Scheele references ancient perspectives from historical figures like Herodotus and Tacitus, who illustrated the Saharans as ungovernable and perilous.

For example, the Garamantes, an ancient society in Libya, were long misunderstood until recent excavations unveiled a sophisticated urban civilization complete with defensive structures, advanced irrigation systems, and public facilities, contradicting the nomadic barbarian stereotype. This connects with Scheele’s discussion regarding Timbuktu as a historical center of learning, known for its scholarly institutions and manuscript libraries.

Her writing about the Saharan people breathes life into the narrative. The fresh and vivid prose captures the essence of her travels, as she engages with a wide array of individuals, from government officials to musicians. Through her explorations, Scheele highlights how livelihoods in the Sahara are intricately tied to mobility, connectivity, and adaptability, showcasing families that traverse national borders to support one another.

However, the severe droughts of the 1970s and 1980s have left lasting impacts, significantly urbanizing the Sahara and reducing the traditional nomadic lifestyle. Scheele critiques Western narratives about African famines, linking them to the portrayal of chronic poverty, which oversimplify complex realities.

Although academic language permeates her analysis, Scheele often critiques the framing of mobility and poverty that fails to recognize the deep-seated complexities of the region’s human experience. She raises questions about the historical implications of slavery in the Sahara, acknowledging controversies around modern accounts of slave markets in Libya.

If distilled to its essence, her main argument advocates for a deeper understanding of Saharan society and history. However, her conclusion, calling for reevaluation of property concepts based on Roman law, may seem disconnected from her earlier observations. As she explores these multifaceted issues, Scheele challenges readers to reconsider our perceptions of the Sahara and its significance.

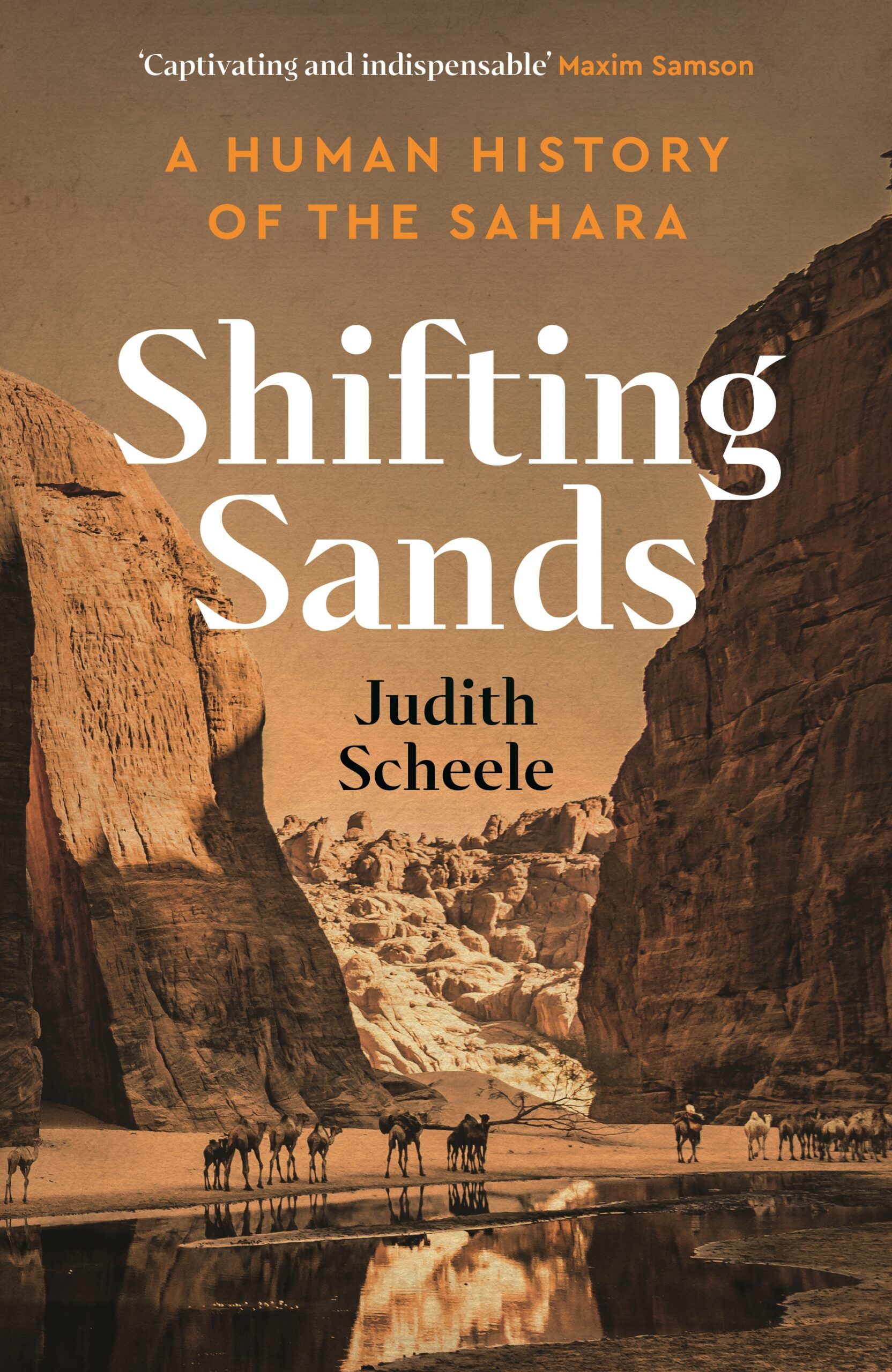

Shifting Sands: A Human History of the Sahara by Judith Scheele, published by Profile Books, invites readers to gain insight into a region often misunderstood.

Post Comment