Geoff Dyer Reflects on His 60s Childhood: Airfix Models and Schoolboy Adventures

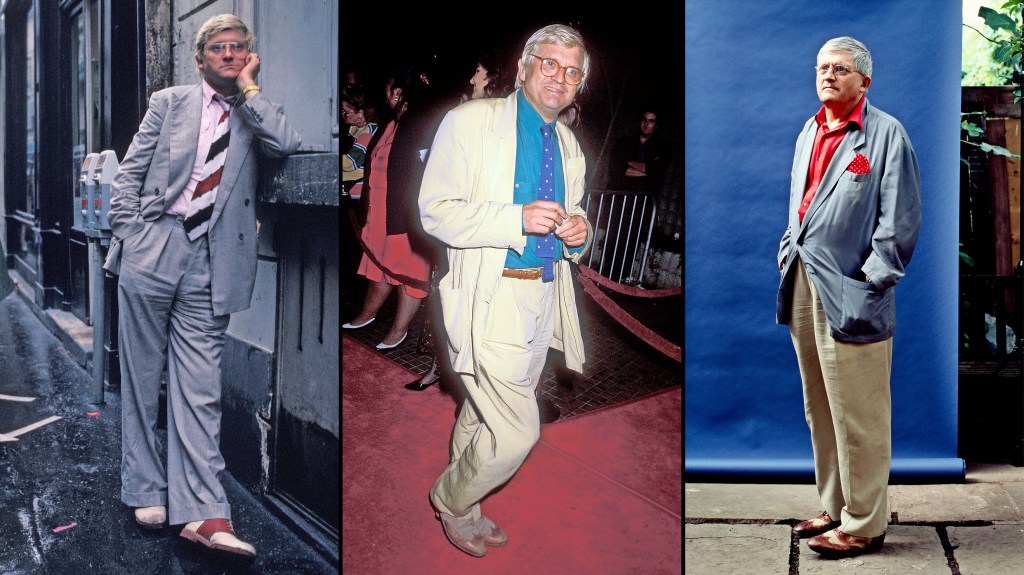

Geoff Dyer, a noted novelist, essayist, and passionate traveler, has explored an array of topics from the Somme’s history to hotel sex, as well as tennis and the works of D.H. Lawrence, often merging fiction with non-fiction in his distinctive style. Over three decades, the 66-year-old has cultivated a reputation as an intellectual figure, with one critic aptly noting, “No one is better than Geoff Dyer at not writing about what he is writing about.”

His latest book, inspired by his wife, art curator Rebecca Wilson, delves into Dyer’s childhood experiences. Wilson, hailing from a “more straightforward upper-middle-class family,” encouraged Dyer to recount his upbringing as the only son of a sheet metal worker and a dinner lady in Cheltenham during the Sixties and Seventies. Dyer agreed that his story was worth telling, and upon sharing the manuscript titled Homework, Wilson described it as “incredible,” a sentiment Dyer humorously reflects on over tea at the prestigious Queens Hotel in Cheltenham.

“She remarked, ‘It’s had an effect on you that I never thought possible.’ I braced myself, thinking it might be flattering, but she quipped, ‘It’s made you even chippier than before.’”

In this memoir, Dyer captures his upbringing in a modest semi-detached house, in a town known for its scenic “Jane Austeny crescents.” He characterizes himself as a “classic product of the postwar settlement,” recounting the NHS’s glory years, the emergence of consumer culture, and the advantages gained from a grammar-school education following his success in the 11-plus exam. This achievement eventually paved his way to Oxford University, illustrating a broader societal transformation in England during that time.

His narrative also reflects his origins in a working-class background within a predominantly middle-class environment. “This town wasn’t marked by the coal strike of 1984. My childhood had no real deprivation, unless you stretch the term ‘deprivation’ to the point of meaninglessness,” he adds.

Dyer humorously wishes for the Cheltenham tourist board to honor him by renaming their annual literary festival as “The Geoff Dyer Festival of Literature.”

When asked about potential invitees to this fictional festival, Dyer, often perceived as avant-garde, reveals he leans towards more conventional literature. He prefers authors like Edith Wharton, Tessa Hadley, and Alan Hollinghurst over Will Self, whom he calls “a dick,” and expresses a dislike for experimental novels that forgo quotation marks.

Though Homework centers on Geoff Dyer, his narrative extends into broader themes. He describes class as “the treacle that gets everywhere in England.” The book paints a picture of Cheltenham with its rusty allotment sheds, reheated school meals, and the charm of family dynamics, including his parents’ frugal habits that extended to practices like turning off their car engine before arriving at their destination. He uses the metaphor of a living room “set aside for best”—preserved for Christmas—while daily life confined them to a cramped kitchen.

Dyer initially attempted to write about his parents following his mother’s passing in 2011 but found it too painful. “However, I collected numerous notes during her final days that became invaluable later,” he reflects. After losing his father shortly after, he felt the responsibility to capture their family life. “As an only child, I don’t have siblings, making me the sole expert on my own life,” he notes, explaining his lack of interest in having children but a fondness for his diverse friendships.

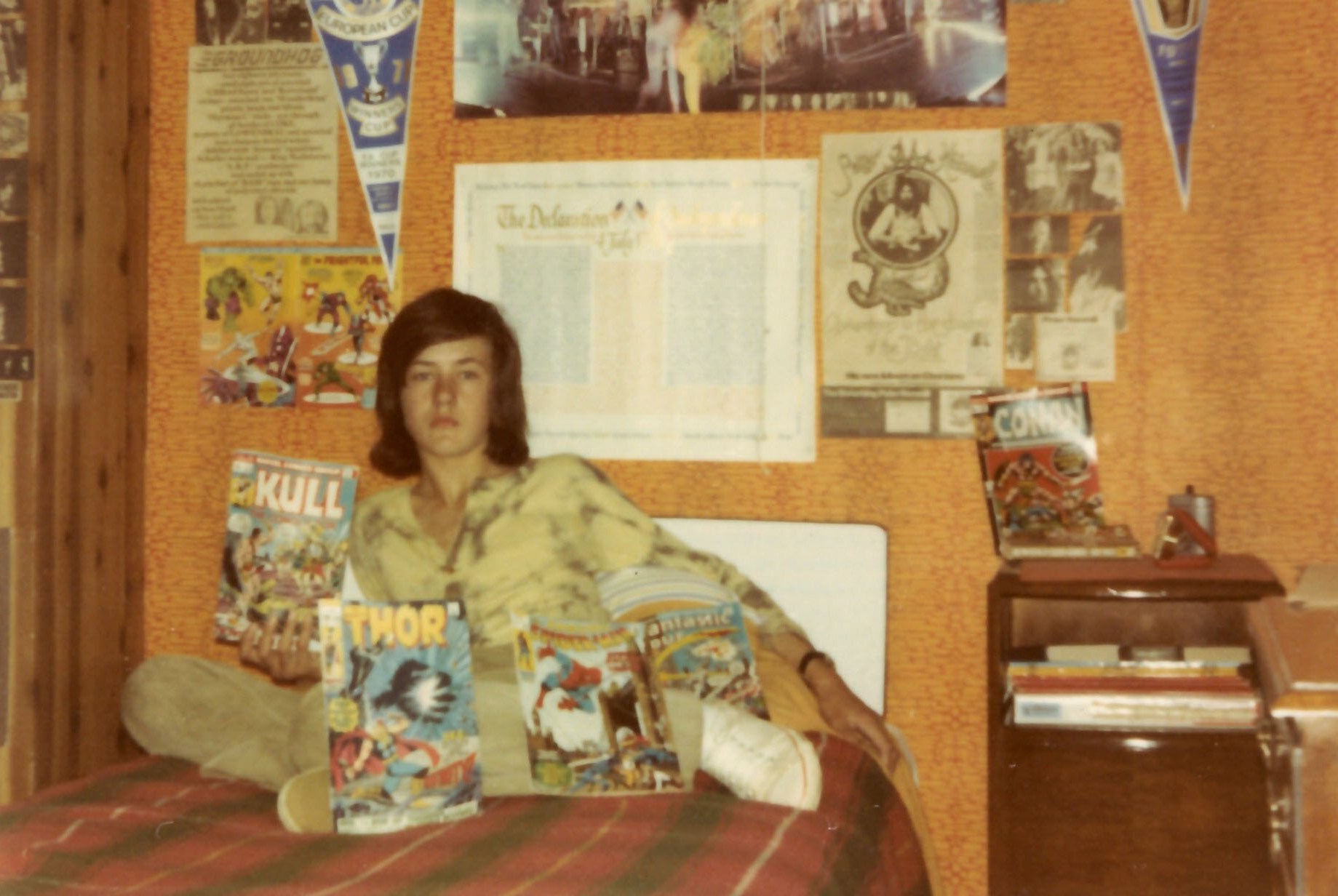

Once he felt emotionally prepared to write, Dyer revisited his youthful writings, which he amusingly described as “miraculous” in their survival despite their lack of quality. Noticing that his memories blossomed from vague to vivid as he wrote, he found inspiration in Wordsworth’s concept of “spots of time,” weaving in memories of 60s toys, ailments, and childhood escapades with his friend Liam Lawless.

Though nostalgic, Dyer insists, “I don’t have a nostalgic bone in my body. I’m simply providing the raw materials for nostalgia.” He carefully navigates the potential to sentimentalize his parents, candidly discussing his father’s modest prejudices, which he believes would have dissipated had circumstances changed. “If a black family moved in next door, I bet within days he’d overcome his initial reluctance,” Dyer muses.

Young Dyer’s own snobberies shine through in his adolescent attempts to “gentrify” their family room, clearing away his mother’s decorations for a bookshelf display above the electric fireplace. His parents’ acceptance turned into a humorous defeat as the decorations eventually returned to the room.

After tea, Dyer leads me on a journey through his Cheltenham, stopping at his childhood home on Fairfield Walk, now transformed with modern renovations, and visiting Naunton Park, his primary school where his mother served as a dinner lady. He attributes his educational divide to passing the 11-plus, referring to it as “the most significant moment of my life, not just then, but for its entire duration.”

Often, disappointment is the comedic core in Dyer’s writing—his misadventures include missing the northern lights and finding the ocean in Tahiti disappointingly calm. Even friend Steve Martin has noted that Dyer is most lively when voicing complaints, a sentiment he supports. However, Dyer wishes to convey his gratitude for the fortunate historical moment that shaped his life.

“I was incredibly fortunate to receive free education, healthcare, and university support. Upon arriving at Oxford, I felt wealthy when I bought my first stereo. I graduated without student debt and enjoyed a seamless transition from university to a happy life on benefits in the Eighties. It was a wonderful experience,” he shares.

While his parents took pride in their self-sufficiency, they struggled to understand their son’s embrace of state aid, viewing it as a marker of his middle-class bohemian success. Dyer reflects pessimistically on the American landscape after living there for several years, noting that his romantic vision of California has dimmed. “As a result, I found England taking on a brighter glow of Blakean Albion in contrast,” he admits.

Content with his return to Ladbroke Grove in west London, Dyer quickly critiques the service culture and expresses a cynical view of life in the UK. Yet he reminds me that, as expressed in his 2016 work White Sands, trials and disappointments only show his enduring hopes for the world.

Homework: A Memoir by Geoff Dyer (Canongate £20 pp288).

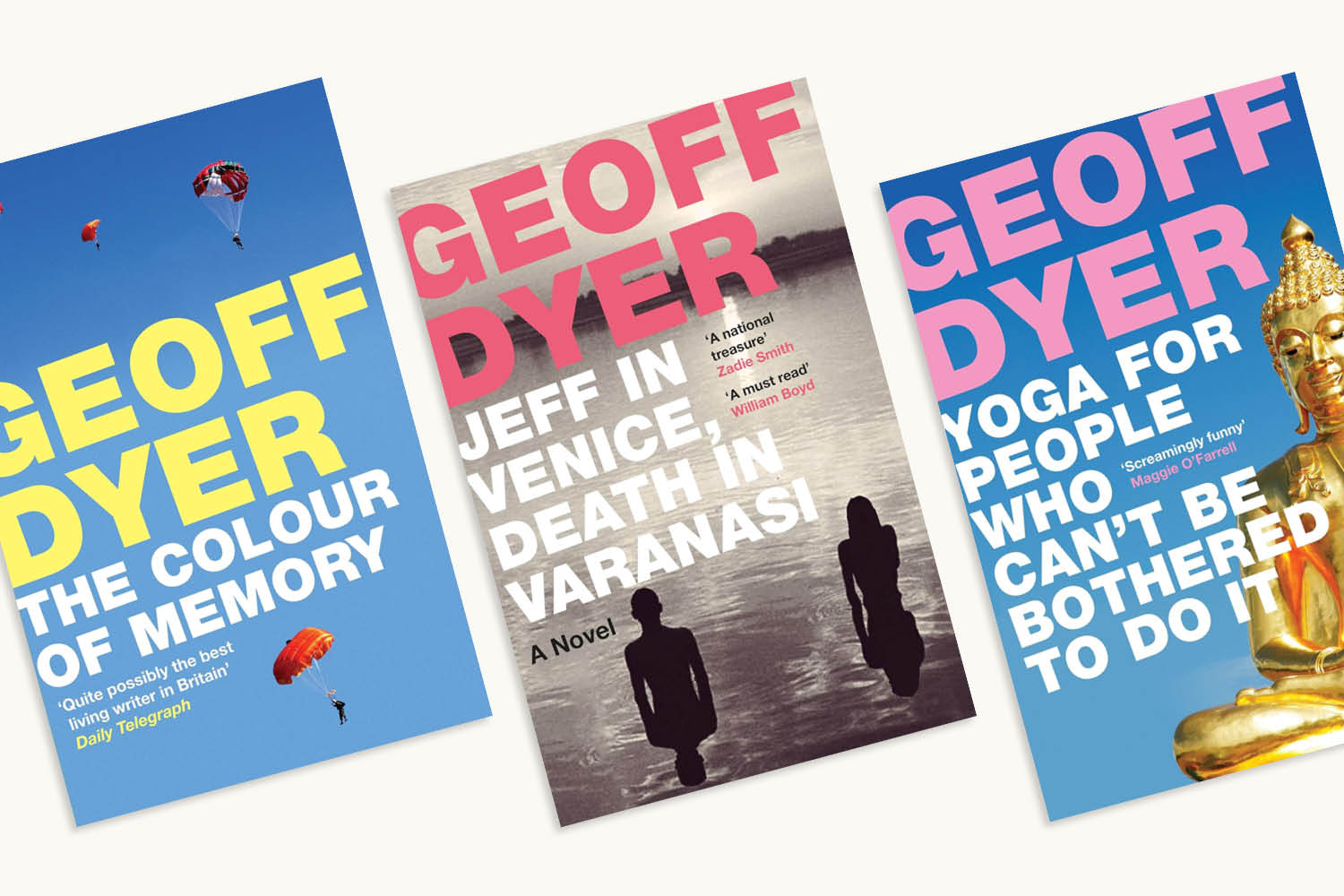

Dyer’s Notable Works

The Colour of Memory (1989)

This engaging first novel reflects on a group of twentysomething graduates navigating life in 1980s Brixton, fueled by youthful rebellion, state benefits, and artistic ambitions. The story weaves humor with a sense of idealism.

Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It (2003)

A comedic travelogue filled with self-deprecating essays, chronicling Dyer’s adventure across the globe in search of profound experiences amid mundane reality.

Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi (2009)

These contrasting novellas explore a writer’s escapades at the Venice Biennale and his introspective journey in India—melding humor, irony, and existential musings.

White Sands (2016)

This collection depicts Dyer’s journeys tracking down artistic inspirations and confronting the paradox of travel’s promise against the backdrop of profound disappointments.

Post Comment