Percival Everett: Disturbing Similarities Between America Today and 1933 Germany

“For a time, even individuals harboring racist views recognized it was unfavorable to be identified as such,” Percival Everett shares. “However, racism has regained its bravado. White supremacist groups are reveling in their resurgence. It’s hard to overlook Elon Musk’s consistent flaunting of arrogance akin to the Führer’s salute.”

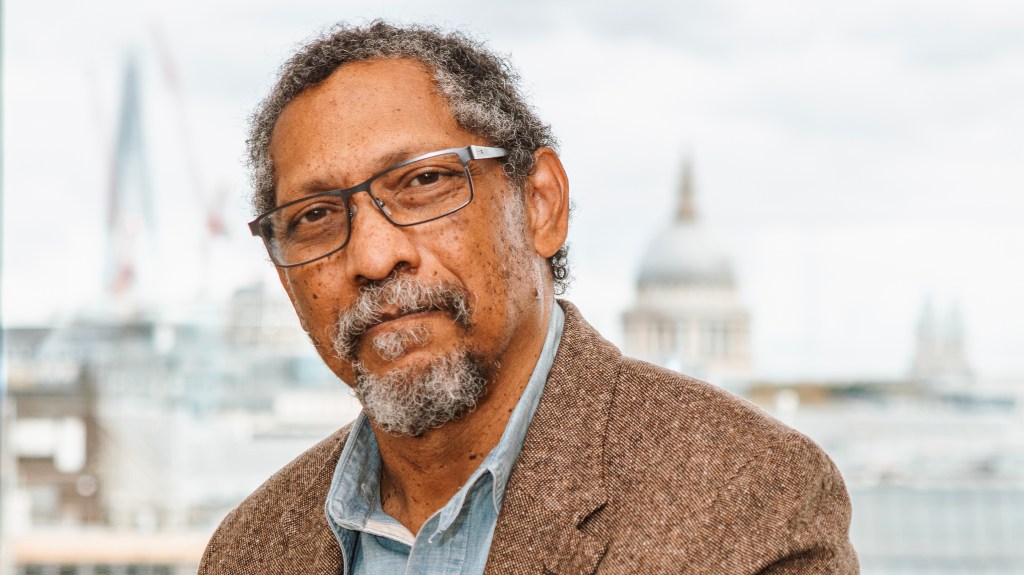

While Everett is generally not a pessimistic observer, he acknowledges that under Donald Trump’s leadership, the situation surrounding racial issues feels like a “one step forward, two steps back” scenario. With decades dedicated to exploring America’s racial challenges and the enduring impacts of slavery, he translates these complex themes into humor-infused novels. At 68, with over 30 books authored, he adopts a tone of wry observation rather than the loud voice of a typical activist.

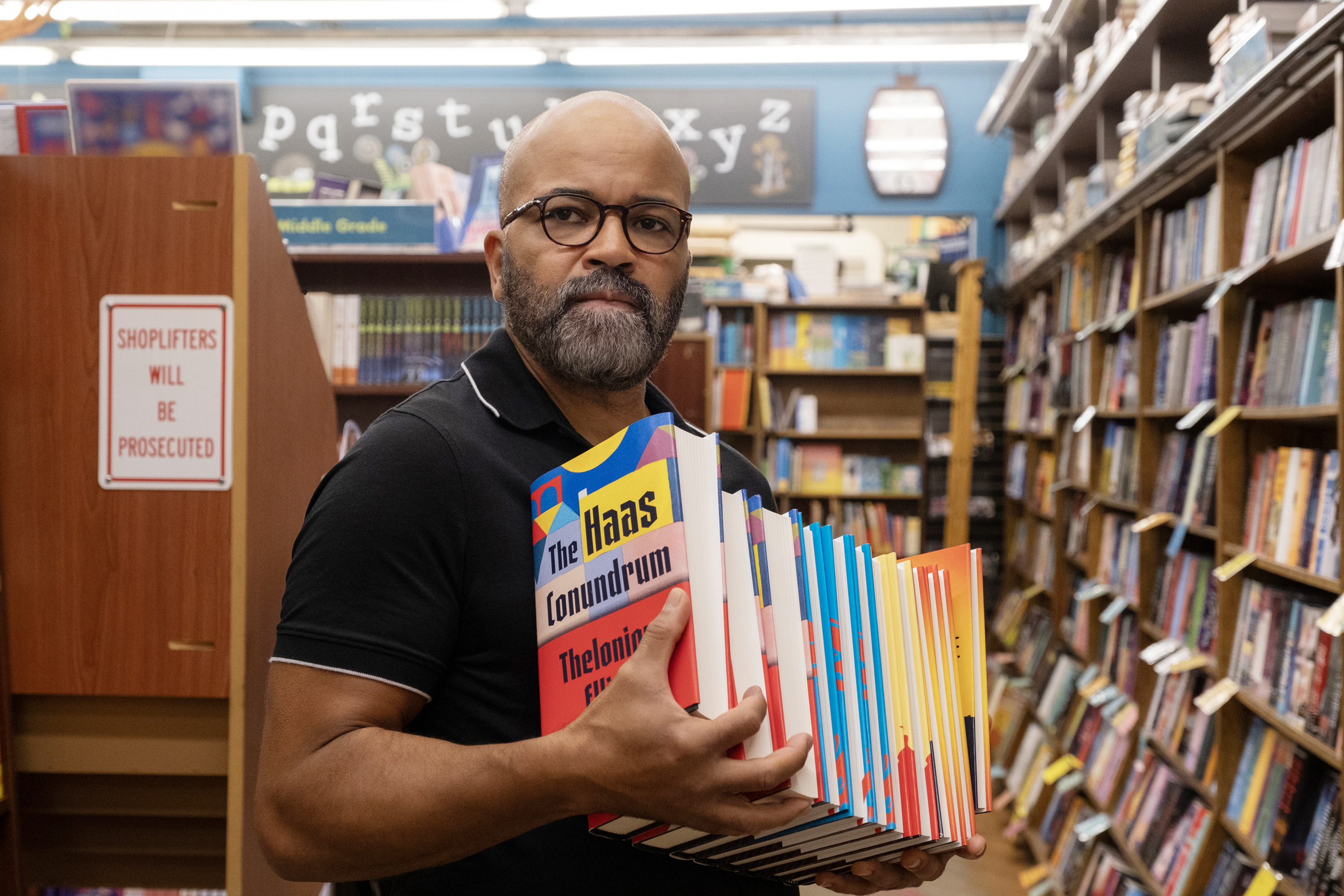

Few authors would dare to reimagine America’s grim history of lynching in a comedic context, as he does in his novel The Trees, where rednecks are ensnared by black zombies. He also satirizes urban literature in an inventive framework involving a Classics-enthused professor penning a book titled My Pafology, which appears in his 2001 novel Erasure—recently adapted into the Oscar-winning film American Fiction, a sharp critique of the literary landscape. His newest work, James, features a hilariously outrageous scene where an African-American character dons “black face” to blend into an outdated minstrel group. Indeed, Everett is unafraid to navigate contentious topics.

This week, he celebrated winning the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for James, a provocative reinterpretation of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, narrated from Jim’s perspective, the runaway slave.

The Pulitzer committee made an excellent decision. It was my favorite read of 2024 and has soared to the top of the US bestseller lists. Why? “It perhaps connects to the pushback against the efforts to erase history that we witness today,” he reflects during our fluctuating Zoom conversation from his home in Los Angeles. “But honestly, I can’t say for sure. If I knew, I could sell that insight to publishers.”

Those forces include Donald Trump, who Everett remarks is an “amazing example of how far a completely incompetent individual can rise.” He finds the nature of the Trump presidency so bizarre that it often defies satire, stating, “It’s so absurd that it leaves little room for a novelist’s imagination. How can you think of anything crazier than this?”

He continues, “The severity of it is alarming. The comparisons between the US today and Germany in 1933 are staggering. We have a populace increasingly lacking in education, where critical thinking about history is actively discouraged.”

As a distinguished professor of English at the University of Southern California, Everett feels particularly affected by Trump’s attacks on academic institutions, such as the administration’s withholding of funding for Harvard University.

“I’ve consistently maintained that popular culture would benefit more from intellectual heroes rather than mere superheroes. In the past, many lower-income individuals, especially poor white families, aspired for their children to attain a college education. Now, universities are viewed as the enemy, associated with elitism.”

“Some of this can be attributed to liberals,” he adds. “They’ve often dismissed those who supported Trump rather than engaging with them. However, how does one effectively converse with individuals who are irrational and uneducated? It’s an immense challenge. They are being swayed by those devoid of moral integrity, interested only in leveraging them for their own selfish agendas.”

When asked if he has read JD Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy, which recounts his impoverished Appalachian childhood, Everett states, “No, and I have no intention of doing so. My understanding of him comes from observing his actions. He is deceitful and lacks a moral hub. He has capitalized on his past for financial gain and is now willing to abandon it for a taste of power.”

While discussing serious themes, Everett maintains a sense of humor, referring to himself as “pathologically ironic.” He expresses admiration for Mel Brooks’s 1974 comedy western, Blazing Saddles—renowned for its satirical approach to race. “Blazing Saddles addressed racial issues with a depth of intelligence that’s hard to find today. It had the freedom to poke fun at serious problems. I wonder if Brooks would be able to make it in the current climate,” he muses.

“Humor and irony have historically helped people endure dark times,” he explains. “Even amidst horror, there were moments of levity in the death camps as individuals found absurdity in their plight. This is how we navigate grim experiences—can you imagine if we were earnest all the time?”

He believes serious subjects like slavery can be treated with a light-hearted touch. He expresses deep appreciation for The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which he has read multiple times. Many educational institutions avoid teaching it due to its racially charged language. Should it be part of school curricula? “Absolutely. It’s the first narrative to feature a character representing an adolescent navigating the defining issue of American history—race. This makes it vital.” Remember, the 13-year-old Huck grapples with the reality that his friend Jim is someone else’s property.

“In numerous ways, [Twain’s novel] could be perceived as offensive, but should that prevent us from reading it? There are plenty of novels portraying women in ways that can be deemed less than fair, yet we keep reading them. The term nigger, it’s merely a six-letter word. What’s there to fear? Its power is not inherent. In Huck Finn, it’s contextually and historically appropriate. If I wrote a novel reflecting real life and had a racist character using the ‘n-word,’ how could anyone believe the rest of the story?”

Publishing often finds itself entangled in such controversies. Erasure skillfully critiques the expectations placed on the types of narratives that Black authors should produce, whether stories from an urban setting or tales from the antebellum era. Everett has never confined himself to these pigeonholes, which may explain why he gained widespread recognition only in his sixties. His literary range is diverse—ranging from Glyph, a 1999 novel narrated by a philosophical baby genius, to Frenzy (1997), a retelling of the Greek myth of Dionysus; and God’s Country (1994), a western parody; and I Am Not Sidney Poitier (2009), which tells the story of a man with a name that evokes a famous actor who was adopted by media tycoon Ted Turner.

“There’s a particular scene in Erasure that draws from my own life,” Everett recounts. “An editor at a gathering asked me, ‘What connection does Dionysus have with Black people?’”

“I believe there’s been improvement, with broader representation emerging, but the expectations remain persistent and subtle. A filmmaker friend of mine, who achieved success with a drama, continues to receive unsolicited offers to create biopics focused on George Floyd, which have no relation to her own interests or artistic direction.”

He highlights that publishing has adopted a narrative suggesting a monolithic “African-American experience,” neglecting the rich and varied realities similar to white America. Conversations about the white American experience seldom occur unless in the context of someone venturing into a challenging neighborhood.

American Fiction received an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. With a discerning perspective, Everett approached the Oscars with a sense of anthropological curiosity, recounting, “Sometimes these award shows feel like an exploration.” He and his wife, Danzy Senna, also a writer, attended the after-party but left shortly after, saying, “Let’s go home.”

He perceives himself as somewhat of a public figure now, stating, “I haven’t reached the level of semi-fame yet; I’m just mildly present in the news. That’s sufficient for me. I would prefer to be absent from the headlines altogether and enjoy the small cult following I’ve heard about—the 15 people who buy my novels.”

Even with the Pulitzer win, he remains unphased. “Winning an award is wonderful—winning one every week would be even better—but comparing works of art is always a tricky endeavor. If the judges had convened on another day, perhaps someone else would have taken home the prize. And that’s perfectly okay.”

Everett has received two nominations for the Booker Prize—for James and The Trees—but he remains indifferent to the prestige of literary awards. Ironically, he expresses pride in winning the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for comic fiction for The Trees, largely because it involved a pig named after the winning novel being brought to his home. “They organized for the farmer to deliver the pig to my residence. They constructed a pen in my front yard, and the pig made itself comfortable on my porch. It was quite a charming pig.”

Awards can be beneficial if they stimulate interest in fiction that enriches empathy and expands imagination. “Reading is one of the most subversive activities, which is why I am passionate about books. Engaging in a book club is another subversive act, fostering discussions about the meanings we derive from stories. Just picture the image of elderly ladies quilting, engaging in lively discussions about books in their clubs, blissfully transitioning from sewing to activism.”

“The most touching compliment I received regarding James was from a woman who told me her Republican father changed his views after reading it. Hearing that was far more rewarding than knowing how many copies sold. Ultimately, that’s the purpose of creating art—to touch someone,” he says.

When confronted with the earnestness of his statement, he jokes, “Don’t let anyone know I said that; it would tarnish my reputation.”

Percival Everett will discuss The Myth of Authenticity at the British Library on June 16.

Curriculum Vitae

Born: 1956, Fort Gordon, Georgia; son of a dentist

Education: Philosophy BA from the University of Miami

Career: His debut novel, Suder, was published in 1983. Notable works include Erasure, The Trees, and I Am Not Sidney Poitier. His recent work, James (2024), has earned the National Book Award, Kirkus Prize, Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. It was also a Booker Prize finalist and contender for the PEN/Faulkner Award. He is a distinguished professor of English at the University of Southern California and has also worked as a rancher, training horses.

Family: Married to writer Danzy Senna, who teaches literature and creative writing at the University of Southern California. They have two sons, aged 18 and 16, along with two dogs.

Quick Fire?

Huckleberry Finn or Tom Sawyer? I dislike Tom Sawyer. He’s such an insufferable character when he intrudes into Huck Finn’s tale.

Golf or snooker? Snooker. As Mark Twain noted, “Golf is simply a good walk spoiled.”

Anora or Conclave? Neither. Anora feels like class elitism. “Look at the poor low-class girl—let’s pity her.” Conclave was merely tedious; it took longer than it needed to.

Pulitzer Prize or Booker Prize? Neither. The Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for comic fiction reigns supreme.

Post Comment